The 2018 flu season was one of the worst we’ve seen in recent history. The CDC reported that 80,000 people died as a result of flu symptoms. That is a staggering number and healthcare organizations are challenged to keep their health plan members engaged, healthy, and motivated to get flu shots, but it’s not as simple as it may seem.

I sat down with Matt Swanson, one of Revel’s human-centered design experts to talk about the different ways behavioral research can help to understand why some people get flu shots routinely, what’s influencing others from getting one at all, and what health plans can do to drive member engagement when it comes to the flu.

Listen to the full interview on RadioRev:

To start, tell me about your role at Revel.

I lead the behavioral research team here which is a blend of qualitative, generative design research within applied behavioral science. We work in close partnership with the data and analytics team. Essentially, my team generates hypotheses and works to understand qualitative things about human beings and the data team applies those to the programs that we run. Together we measure the outcomes to see where we’re wrong, where we’re right, and how we can better engage with people moving forward while optimizing our system.

When people hear a statistic like “80,000 people died from the flu last year”, do you think numbers like that have an impact on behavior?

The short answer is people are so different in how they interpret things like this. The number 80,000 is tragic and seems to have gotten the attention of a lot of people—it certainly plays a role in what a slice of the population will do. Facts like this can be helpful, especially when they are repeated, but does it have a direct impact on behavior? It’s hard to say—people have such diverse motivations.

I’ve heard you say before that “we can’t fact people into action.” What do you mean by that?

I’m intentionally poking the bear with that statement. We work in a really interesting and challenging industry and I work to create something that is going to influence someone’s behavior. One of the challenges we have is the central role of regulation and clinical evidence. Those things are really important and amazing tools that have given us huge advances in how we work, but they can’t do all the heavy lifting.

Facts and evidence aren’t personal—they don’t have any concrete meaning for an individual. For example, people don’t really care about their BMI, they care about feeling good about themselves. People don’t really care about their blood pressure, they care that their doctor says that they’re healthy. They care about feeling well enough to go on a hike, do some gardening, or make it to their grand daughter’s wedding—things that they enjoy and affect them personally.

There’s such an anchor on statistics that matter in population health, but it’s hard to explain to someone who doesn’t intimately understand how healthcare works that if enough people get a flu shot as a country we will spend less on healthcare, as a country fewer people will have complications, as a country fewer people will die. That isn’t always effective because what matters to people is typically more personal than that.

The bottom line: facts don’t convince people. They may work for some people, but different things motivate different people and it’s my job to understand what those differences are so we can help health plans and providers engage their members and patients more effectively.

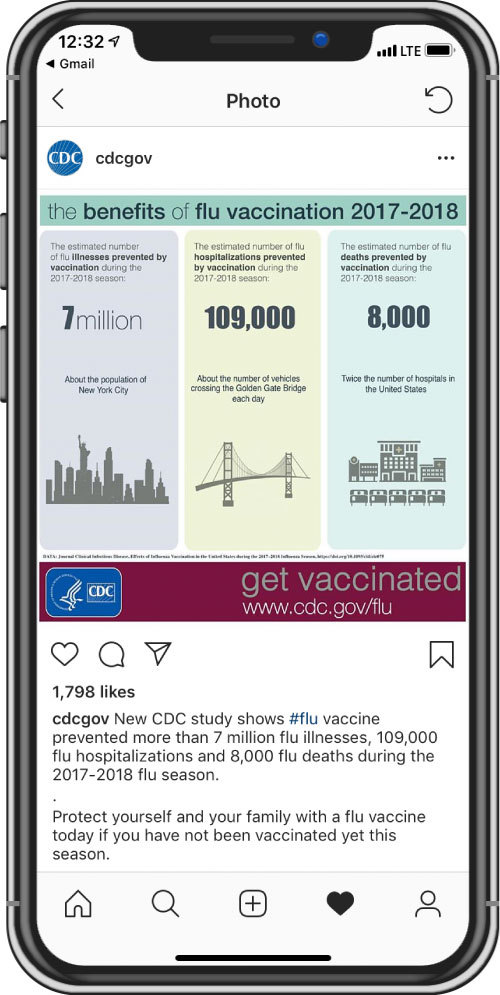

The CDC recently posted an infographic on their Instagram that showed the benefits of flu vaccination in the 2017-2018 year with some heavy hitting stats. They related the large numbers to the population of New York City, the number of cars that cross the Golden Gate Bridge, and the number of hospitals in the United States. What is your reaction to this approach by the CDC?

This is really interesting because as I mentioned before we find that facts and statistics don’t typically work when you are trying to get someone to do something. It’s not that they don’t have a role, but they aren’t the pivot point that is going to get someone to change their mind.

There are a few really good things that the CDC is doing here. The number 7 million on it’s own is meaningless, but when you tie it to the population of New York City you give people something concrete to hold on to. When you say twice the number of hospitals in the United States, that means something. You start to imagine the people inside those hospitals and what they might be going through. That becomes an image in your mind, an impression, a potential motivation to do something. It’s a lot more effective when you tie numbers to a reality people can grasp.

I’d like to switch gears and talk about the flu research you’ve done. Can you walk us through the program?

We focused on having conversations with people in the Medicare and Medicaid populations because the flu vaccine is measured in those populations. We interviewed a variety of people from all walks of life—went to their homes and saw what their life was like. They talked to us about what’s important in their life, aspects of their health, and a little bit about the context of their health—if they had a doctor, if they had insurance, what it felt like when they were healthy or sick. We asked questions about what they do when they are sick, who matters around them when they get sick, and the consequences of being sick so we could start to contextualize and understand where the flu shot fits in.

For example, we spoke with a man living in a group home who is recovering from an opioid addiction. He just started a new job that he’s excited about, he’s focused on attending meetings and getting his life back, and you can really tell that it takes all his energy to hold these pieces together. His belief is that if he gets a flu shot he’ll get sick. You can quickly see that if he believes that getting the flu shot is going to make him sick, even if it’s for a little bit, he may have to miss work and it might lead him to lose his job, which might lead him to lose his place in the group home, which could lead back to using and lose all the progress he’s made. Understanding this belief and what the stakes are for him is critical.

Another person we spoke to was really interesting because everything in her life revolved around her Italian identity—the food she eats, the community she spends time with, and the social aspects of her life—those things are what she identified as key to being healthy. She said, “I don’t want any shots. I think a good glass of red wine is better than any shot.”

As you can see just from these two examples, understanding values and beliefs around health are critical to understanding people’s motivations and why or why not they may take specific health actions.

Was there anything you heard during these interviews that surprised you?

Absolutely. It was a random sample, but we ended up talking to a lot of people who would never get a flu vaccination or any type of vaccination for that matter. What surprised me is that I thought I understood the reasons why going into the interviews, but it ended up being a much more diverse set of perspectives.

Thinking about the organizations that Revel serves—health plans and providers—what are the challenges when it comes to engaging members to take preventive health actions, like getting a flu shot?

When you work in this industry you go so deep and you know so much about healthcare, it eventually becomes a part of who you are. It starts to align with your morals and you begin to think “if our members, if our patients knew what we knew, they would believe what we believe” or “we just need to educate people.” This is true—awareness is important, but there’s a big gap between awareness and action. And there’s a lot of beliefs and values that come into play that we need to consider. Not every member is going to engage in the same way—not through the same channel or message—we need to dig deep and really understand individuals to achieve engagement and ultimately drive action.

From a health plan perspective, how are these insights actionable?

It’s a big question. What we find is that different messages work differently for different people. I would advice health plans to not just send one mailer, one kind of email, or make one kind of call when trying to engage their members. It’s often the combination of channels and messages that end up creating the spark. I know it’s hard, but as an industry we need to start advancing and leveling up the spectrum of communication to message to an individual’s state of mind and meet them where they are.

It sounds like personalization is the way to win.

Exactly.

You’ve done all of this incredible research and have talked to so many different people with different perspectives. How does that help you to do your job more effectively—or does it muddy the waters?

It absolutely helps me because I’ve learned to insert reality into communication, into technology, into how we run things here at Revel. It’s certainly more complex and it’s harder, but it’s more meaningful. It makes me excited about what we’re doing.

For more from Matt, connect with with him on LinkedIn.