Treatment for mental health is antithetical to physical health. Distinct from the health impact, it’s laden with societal and cultural assumptions and judgment. Mental health treatment can be viewed as nebulous, not readily visible, and the efficacy normally not expressed through any external evidence of healing.

“Helpful advice” is provided by friends and family as a way to get through an illness that requires medical attention. It’s no different than an individual with the flu being provided the advice “shake it off.” Mental illness is treated as something that is within an individual’s control; although it is no different than a medical condition over which we, in most cases, have little control except through medical intervention.

The State of Behavioral Health—The Facts

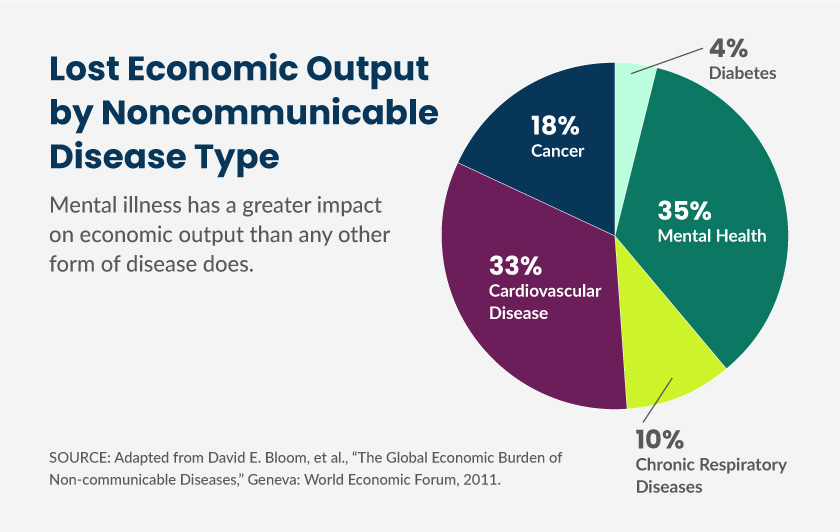

- According to the World Health Organization, mental illness represents the biggest economic burden of any health issue in the world

- 1 in 5 adults experience a mental illness

- Major depressive disorder affects approximately 14.8 million American adults or about 6.7% of the U.S. population age 18 and older in a given year, with the median onset being age 32

- Half of the people with depression appear happy

- Approximately 40 million American adults ages 18 and older, or about 18.1% of people in this age group in a given year, have an anxiety disorder

- An estimated 16.2 million adults, or 6.7%, have had at least one depressive episode in a year

The stigma is being challenged through an increased awareness, acceptance, and understanding. Expanding numbers of public figures are acknowledging and speaking about their own struggles and generating normalcy and acceptance around mental illness on par with physical illness. However, the mental health paradigm continues to shift in a way where diversity in diagnosis, acceptance, and treatment becomes more attuned to meet an individual where they are “at” versus forcing into a prescribed system diametric to actual needs.

As the industry continues its evolution, we’ve identified 4 factors that are having a major impact on behavioral health engagement.

1. The Challenge of Access

Fact: 89.3 million live in a mental health shortage area

Increasing numbers of mental health providers are retiring or exiting the profession. The rate of entry falls short of those leaving and the U.S. is seeing a growing shortage—the statistics around this are staggering. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, approximately 111 million people live in mental health professional deserts. A 2016 report released by the Health Resources and Services Administration projected the supply of workers in select behavioral health professions to be approximately 250,000 workers short of the projected demand in 2025.

Access is precipitously declining and limited although the need for providers is rapidly growing. 6 in 10 Americans have sought or wanted to seek mental health services for themselves or a loved one, but access creates a barrier. In a similar study, only 1 in 4 believe mental health services are accessible. These access restrictions are a function of several dynamics. First, geographic density is decreasing with 46% of Americans having to drive longer than an hour to access care. However, this number pales in comparison to the fact half of the counties in the U.S. have zero psychiatrists. Individuals are also beginning to engage in emergency room boarding since the lack of access can quickly culminate in a mental health crisis.

96 million Americans have had to wait longer than one week for mental health treatments. This is an underestimate since in many areas the wait can be up to 14 weeks. Even at the point where an individual is able to schedule an appointment and see a mental health professional, there is a question of whether there is a “fit” between the patient and mental health provider. It’s critical that a patient is comfortable and can confide in the therapeutic environment. If it falls short, a patient will likely need to restart the process and incur an additional wait and delay in accessing mental health services.

Irrespective of geographic and wait-time barriers, there is confusion in what type of provider may be appropriate. Some individuals view their primary care provider as a first-line therapist, while others may prefer a direct referral to a psychiatrist. There are Ph.D, Psy.D, marriage and family therapists, social workers, individual therapists, health coaches, etc. 60 million people who have not sought treatment wouldn’t know where to go if they needed it. This lack of clarity further complicates the effort in gaining access to care.

2. The Impact of Stigma

Mental health is nebulous and, in many cases, invisible to most. In addition to the barriers created by access, its abstract persistency (unlike the visibility with a broken arm) encourages individuals to forego treatment under the guise that it can be addressed without professional help. Forgoing treatment can also be due to the fact that Americans believe depression is a sign of emotional or mental weakness. To that end, 1 in 5 kids has a mental health condition and 85% go untreated, and 56% of Americans with mental illness do not receive treatment.

Unlike a physical illness, treatment can be stigmatizing. Individuals may be afraid, anxious and/or embarrassed about needing the help. 1/3 of Americans have worried about others judging them for seeking treatment and over 1/5 have lied about to avoid telling people they are seeking treatment. This fosters shame and exposes a hidden suffering where the impact is not discussed and treatment may be disregarded.

Practically, the impact on kids of the mental health stigma is amplified. For example, to go to a mental health provider kids are forced to choose between missing school, or if they are fortunate to get an appointment after school, potentially may need to miss after school activities such as sports practice or games. Schools are much less forgiving about missing school for a weekly therapy appointment, than a chronic medical condition and there can be more shame associated with reporting absence for a therapist appointment.

However, attitudes and perspectives on the need for mental health treatment are starting to be recast. There have been hundreds of articles, television segments, and celebrities lifting the “mask” and speaking out. Consistent with this, 76% of Americans believe mental health is as important as physical health.

Mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety, can lead to heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and other chronic health problems. Depression can produce signs of increased inflammation, changes in the control of heart rate and blood circulation, and abnormalities in stress hormones.

Slowly mental health is becoming recognized as co-occurring with physical illness and driving some of the heightened awareness and increased intervention. Until the headwinds associated with the stigma fade, the barriers to care will continue to exist and perspective of those who suffer skewed.

3. The Economic Cost of Mental Health

Cost is the #1 barrier to mental health care, and 1 in 4 have had to choose between mental health care and daily necessities. Americans report cost and poor insurance coverage as the top barriers for accessing mental health care (42%). According to a 2014 study, only 55% of psychiatrists accepted health insurance compared to 89% of all other healthcare professionals. It is untenable for most people to afford the out-of-pocket therapist costs where a copay for coverage can be approximately $30, but full out-of-network coverage typically ranges from $50 to $240 per session.

It’s axiomatic the lack of parity in reimbursement structure between mental and physical health. While the mental health parity law was signed with the promise to make mental health and substance abuse treatment just as easy to get as care for any other condition, this goal is fractured by industry structure, treatment paradigm, and health care systems. Under this law beneficiaries should receive the same level of coverage for behavioral (mental health and substance use disorder) services as for medical and surgical services.

This was further reinforced by the ACA making it an “essential benefit” to be covered by health insurance. However, this law had no bearing on reimbursement levels. There are escalating numbers of providers opting to only take private (full out-of-pocket payment) pay patients since they often cannot offset their costs with insurer reimbursement rates. This has forced insurance networks to narrow and patients to be burdened by either high costs or sacrificing care.

Last, the cost to society for mental illness is large, having a greater impact on economic output than any other form of disease. This impact is further amplified by the fact that mental illness is the number 1 cause of disability. Short of that, mental illness can affect abilities, confidence levels, ability to concentrate, and make decisions. “Presenteeism” can also impact team dynamics and relationships. The cost to the economy for failing to treat creates a business impact, but also an economic impact in loss of income, increase in out-of-pocket costs with expanding co-morbidities, and depletion on the intrinsic value of life.

4. The Response of States

Mental Health America ranks states on 15 measures, including both adult and youth standards. States are focusing on mental and behavioral health to a greater extent than ever before. For Medicaid, many states are tying health plan pay-for-performance, incentives, withholds, and auto assignment preference to mental health measures. States are realizing the enormous cost to not treating as Medicaid spending for individuals with a behavioral health diagnosis is 4x higher than those without. To support this, CMS developed a list of 16 behavioral health measures to enable states to make progress towards improvement. CMS has also developed a new Medicaid demonstration to expand mental health treatment services.

There are a handful of states that are adopting value-based payment models to support mental health care. The following are examples of several state initiatives:

Arizona

Adopted an integrated behavioral health model tying 5% of payments to value-based mental health strategies. Plans may choose one of five strategies:

- Incentives tied to care coordination

- Pay-for-performance

- Bundled payments

- Shared payments

- Performance-related capitation payments

Minnesota

Created the Minnesota State Innovation Model to integrate care and services for the whole person across the continuum of care (including physical health care, mental health care, long-term care, and other services) through a statewide Accountable Health Model. Minnesota’s model includes:

- Creation of “Accountable Communities for Health” (ACHs) that integrate medical care with behavioral health services, public health, long-term care, social services, and other forms of care.

- Expansion of health information exchange and health information technology infrastructure.

- Support for primary care physicians who wish to transform their practices into Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMHs).

Pennsylvania

Adopted a program to integrate behavioral and physical health care services. Three process improvements are tied to 5 performance measures:

- Member satisfaction

- Developing a member integrated care plan

- Coordination of care plays to notify the other of hospital admissions within 1 day.

The 5 performance measures align with the behavioral health HEDIS measures. Payments to plans are tied to improvements in each area.

Addressing the Problem through Identification and Innovation

The industry is beginning to recognize the efficacy of online treatment for certain mental illnesses. One meta-analysis of data from 3,876 adults found those who underwent internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (“CBT”) to treat symptoms of depression had better outcomes than those who didn’t use online therapies and they were also more likely to stick to their treatment.

This market is becoming saturated with the need for consumers to be more discerning. Some are only focused on self-management, training, or symptom tracking while others engage in CBT or other evidence-based therapy.

There are several companies that are innovating with new care models:

- Lyra—uses artificial intelligence to match individuals to the right person for the right care through digital, live, and/or video therapy.

- Concert health—integrates primary care physicians, care managers, and psychiatrists to better coordinate care and create a system approach to addressing mental health.

- Learn to Live—CBT-based model delivering digital and telephonic coaching for a multimodal approach to mental health.

Critical to addressing mental health is identification. Unless an individual self-selects or is referred to a provider, it can be difficult for someone to seek treatment. There may be reticence to acknowledge and being labeled as potentially having a mental health issue. As a result, one excellent way for an individual to start the process is through a health assessment. These are barrierless and low commitment modalities, and include questions focused on leading mental health indicators like stress, worry, family dynamics, and personal relationships (rather than exclusively mental health directed). These are typically administered through a health plan, provider, or through self-selection.

The questions typically embed the industry standard PHQ9 and/or GAD7 framework, so individuals are triaged to the right care. These also can enable the introduction of less invasive, lower-cost, and less stigmatizing resources, such as digital tools. People don’t need to jump from a mental health concern to trying to make an appointment and going to a therapist which may be too much of a commitment for where an individual is in the self-recognition process.

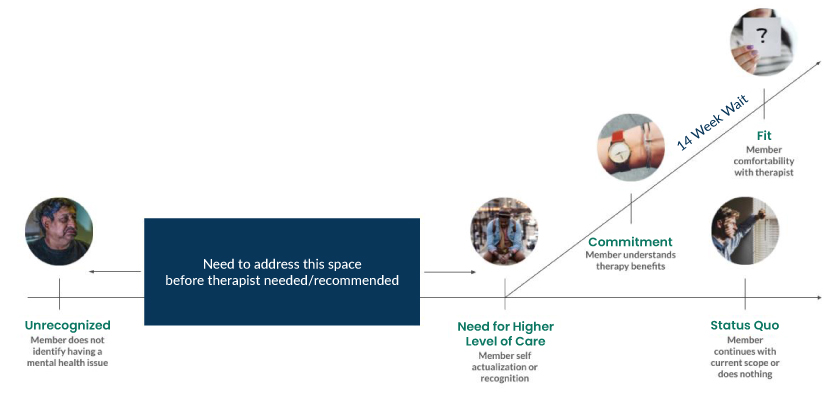

Tables 1 and 2 depict how these processes and tools can function. Table 1 is an example of the current processes. An individual has an unrecognized mental health issue or is a silent sufferer. In many cases an individual is triaged to or self-selects going to a therapist without knowledge of other resources.

This involves many of the barriers described above: potential out-of-pocket costs, time to appointment (averaging 14 weeks), finding the right fit, and therapist availability, demonstrating the limits on receiving consistent treatment.

Table 2 describes identification through a health risk assessment, or similar tool, and layers alternate resources to care before committing to what can often be a protracted, stigmatizing process. Identification can occur through a simple health risk assessment.

From there a personalized action plan helps direct an individual to resources commensurate to where they are in the therapy-commitment and mental health recognition process. Digital or other behavioral health tools can be surfaced to help a member understand the range of care.

To the extent someone acknowledges the need for additional help, the member can access referrals to higher levels of care matching their needs. Others may find self-sustaining helpful tools as the best intervention.

This process enables self-recognition and commitment in seeking further care—it is done on the individual’s own terms, in a way that fits their needs and allows greater self-recognition for therapy. A platform that influences health action (rather than perfunctory engagement and clicks) is imperative.

It is worth noting that there are serious mental health issues that require referrals directly to a mental health provider. Not all processes can follow that outlined in table 2. However, for the majority of people who suffer from adjustment, depression, stress or anxiety, an individualized care plan and continuum can help start the process to mental health help.

What’s Next?

Icario has designed a platform that augments, through what is described in table 2, the quintessential mental health care and referral process. Through a health risk assessment, that is developed to include mental health screening questions, it is able to identify individuals at risk and who may require additional care.

Individuals are provided digital resources to begin their journey in understanding their mental health needs. Digital programs can be referenced that are low investment and allow triage to care managers for higher level concerns. This approach creates optionality for individuals who want choice in how to address any mental health concern.

It’s also a mechanism to eliminate barriers and reduce stigmatization. While these resources may not, and in some cases should not, replace therapy, they create an opportunity to engage. Helping people start to address their mental health issues launches them on a trajectory fostering awareness and commitment in addressing any issues.

With the rise in the number of people with mental illness, increases in costs, and provider scarcity, this approach and resource allocation will continue to become more critical in getting individuals to the appropriate help.